Jan Cheetham and I speak on IoT Systems risk mitigation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Lockdown Cybersecurity Conference in July.

Tag Archives: smart city

Bathtubs, manageability, & IoT

The limited funding and staffing resources inherent in almost all institutions and cities creates a delicate balance between IT systems operations, managing institutional risk, and cybersecurity operations. A critical component to this balance is systems manageability. Implementing unmanaged/under-managed systems can quickly perturb this balance and cause reactionary spending, such as on cybersecurity incident response, institutional reputation damage control, unplanned systems repair dollars, as well as others.

IoT Systems — with their multi-organizational boundary spanning, unclear systems ownership and accountability, lack of precedence for implementation, and high number of networked computing devices (‘Things’) — are particular candidates for unmanaged/under-managed systems in a city or institution.

Systems manageability

IT systems that tend to be more manageable allow for more predictability in an institution’s resource and cashflow planning. Criteria for high systems manageability include:

- having well-defined performance expectations

- thoughtful and thorough implementation

- accessible training and documentation

- strong vendor support

- others

Unmanaged or under-managed systems increase the likelihood of a cyber event such as device compromise or whole system compromise as well as facilitate potentially substantial operations disruption and unplanned financial burden.

Bathtub modeling

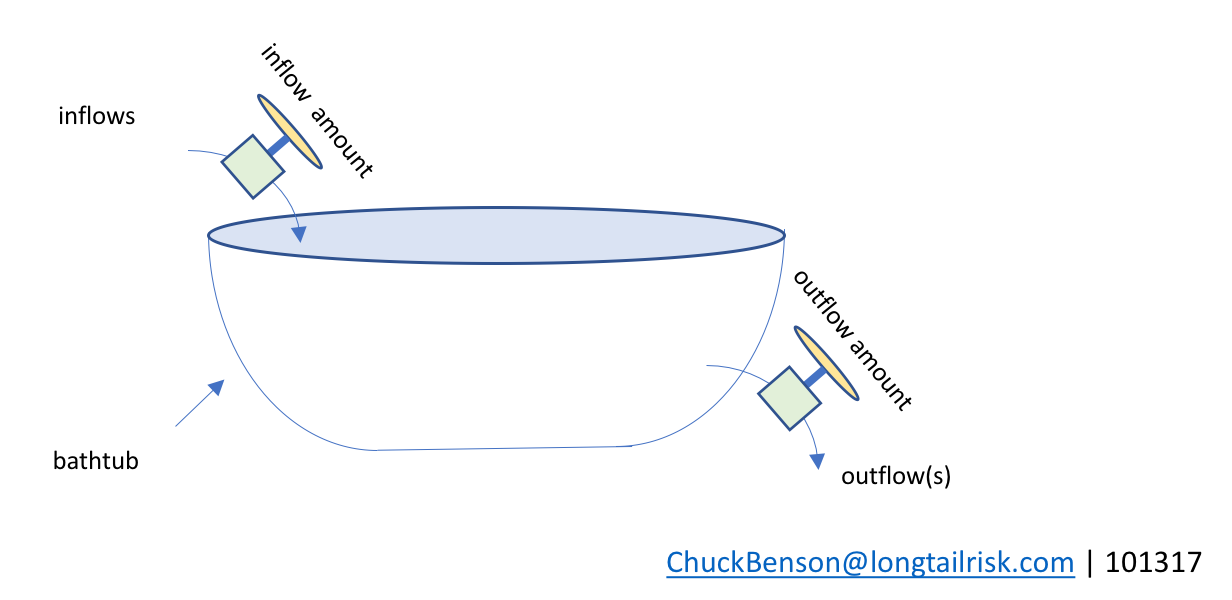

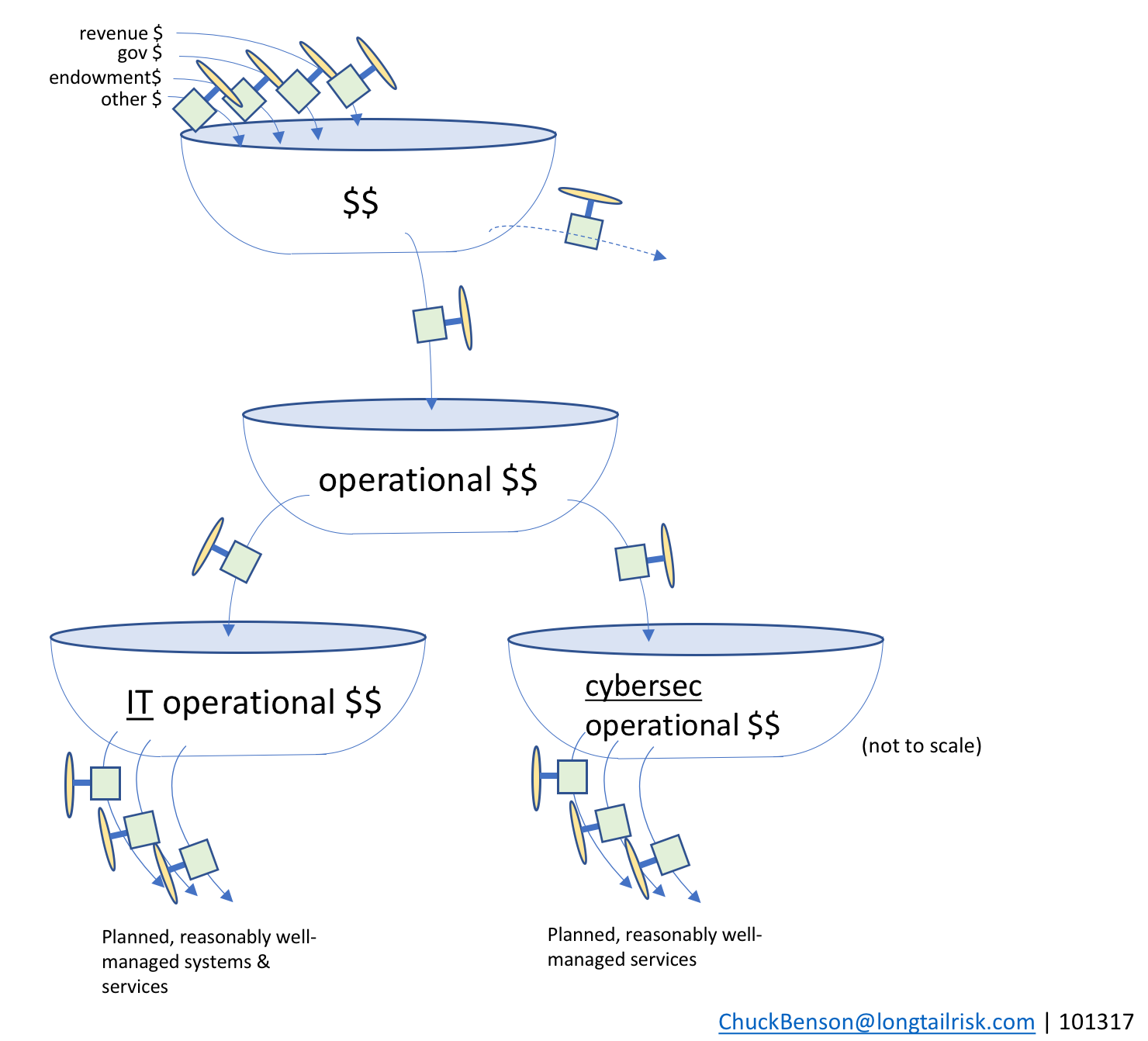

We can use some concepts from stocks and flows diagrams where the stock is represented by a bathtub to create a basic model of resource availability in this delicate dance of balancing of resources for IT systems operations, cybersecurity operations, and managing institutional risk.

My understanding that the use of a bathtub to represent stocks and flows goes back to 2000 when John Sterman and Linda Booth Sweeney published results of an experiment on how people understand and interpret complex systems. On a related note, I found the book, Thinking in Systems, by the late Donella Meadows to be a very consumable and helpful introduction to stocks and flows diagrams.

The idea is that the ‘stock’ is the level of water in the tub. Water can flow into the tub, raising the tub level, and that amount can be varied by some mechanism(s) or external constraints. Similarly, water can flow out of the bathtub, draining the tub, and there is a mechanism for controlling the rate of that outflow. And, of course, both could happen at the same time.

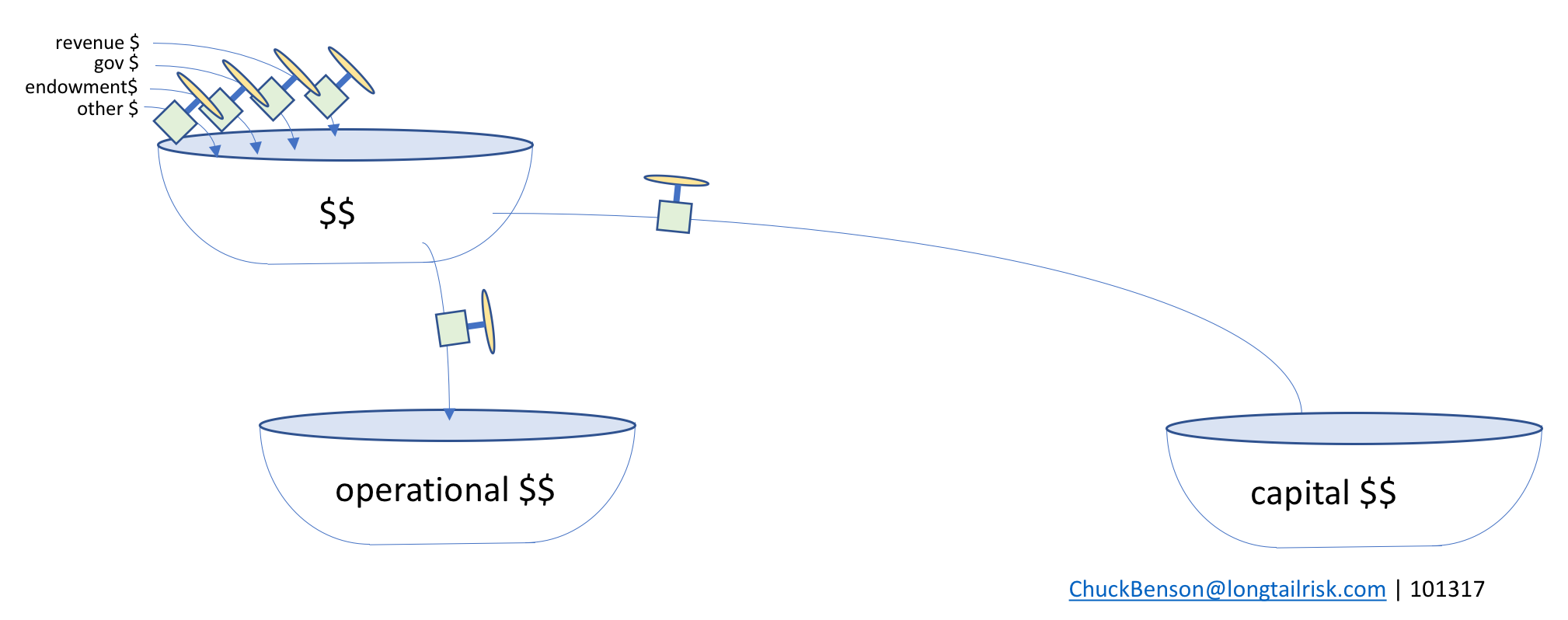

Bathtub of bucks

Now, imagine that instead of water, the tub holds metaphorical dollars. The tub can be thought of as an account, a set of funds, ‘budget number’, set of budget numbers, or similar. The inflows then are one or more sources for adding dollars to that tub with a mechanism or set of constraints that determines the rate of flow into the tub. Similarly, there is a mechanism for setting how much flows out of the tub (spending or investing).

City and institutional spending

Cities and institutions have multiple sources of inflows, most of which they probably don’t control. Those inflows have independent characteristics from each other as well as some interdependencies with each other. The main takeaway is that the city or institution probably does not control a whole lot regarding what’s coming in.

The spending from the top tub can go to multiple places, themselves other tubs. From the top bathtub, most organizations make decisions between operational dollars (running things) and capital dollars (buying or building big things).

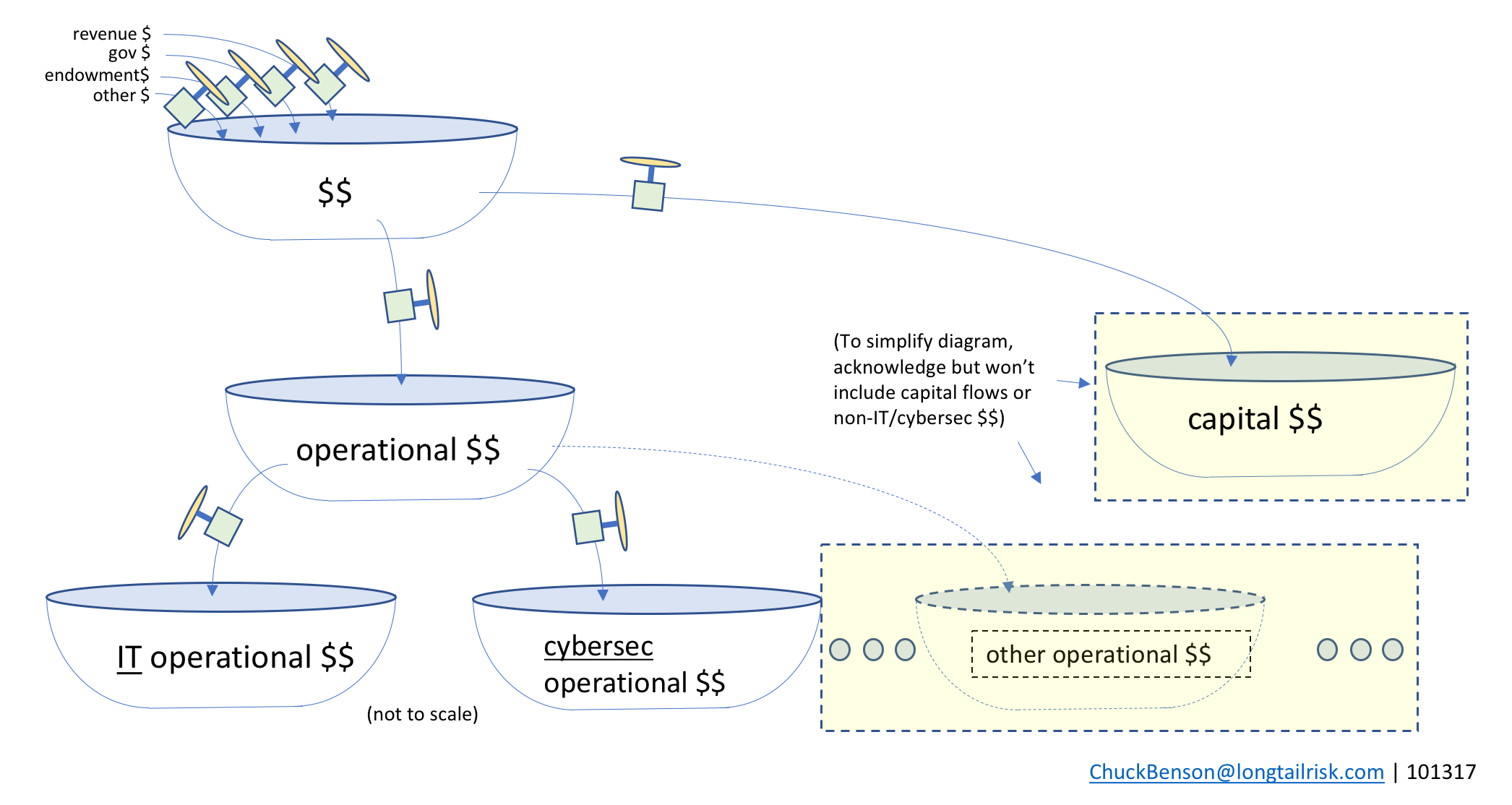

IT & cybersec resources & spending

From the operational dollars tub, some funding goes to IT operations, some goes to cybersecurity operations (eg CISO’s office), and other funding goes to many other traditional and important areas such as HR, finance, policy/law enforcement, and others.

In the interest of keeping the diagram simpler for our discussion, we won’t include capital spending or non-IT/cybersec spending in subsequent diagrams.

IT systems services and cybersecurity services

Funds from the IT operational bathtub are used to resource the management of various IT systems and sub-systems in the institution or city. This includes both on-premise systems as well as cloud-based systems. Examples include enterprise resource management (ERP) systems, institutional learning/training systems, calendaring and email systems, and others.

Systems that have known performance expectations and implementation precedents (either themselves or peer implementations) can provide the basis for a fairly reasonable calculation to be made on required staffing and funding support requirements.

Similarly, the city/institutional department/organization providing information security services (usually the CISO’s office) also has a set of well-managed services that are planned for and delivered. Examples of these information security services might include: education and outreach, incident management capability, privacy policy guidance, intelligence analysis, and others. The CISO’s office will work to develop services and capabilities based on the IT systems that the city or institution is operating, known and evolving threats and vulnerabilities, existing risk levels, and others.

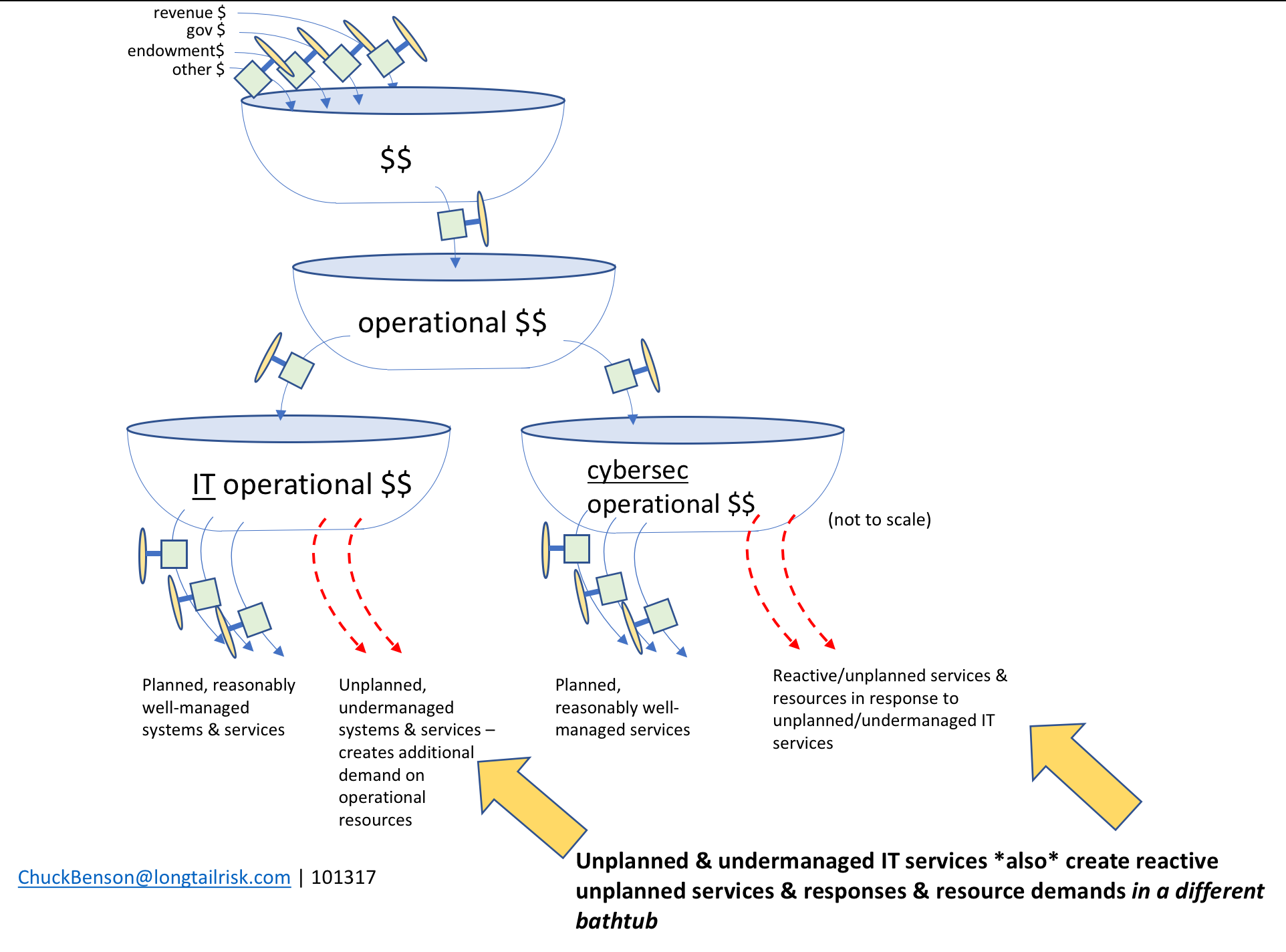

The trouble with unplanned, under-managed, and unmanaged systems

Managing and identifying management support resources can be challenging enough with known systems. Challenges and institutional risk quickly becomes exacerbated though when unplanned or weakly planned systems are added. For example, after the budget/planning cycle, an influential person or group may decide that the city or institution “must have” System X. And then later someone else with influence might insist on (unplanned) System Y.

When these unplanned or under-planned systems are added, several deleterious things can happen:

- the unplanned system drains from the IT operational funding tub in the forms of implementation staffing, management staffing, and support tools

- planned systems now no longer have their expected resources and they themselves can become under-managed in addition to the add-on system that is very likely also to be under-managed

- institutional/city risk increases because unmanaged/under-managed systems increase likelihood of system comprise due to misconfiguration, mismanagement, lack of oversight, failure of (or lack of application of) controls

- things get worse as the problem also transmits to a different bathtub, ie the information security services provider for the city or institution, eg the CISO’s office

- when compromise occurs — particularly on systems that the CISO’s office could not plan for — the CISO’s office is now forced to work in a reactionary mode. This is expensive and pulls resources from planned cybersecurity services

unplanned, under-managed systems also transmit their problems to the CISO’s office in the form of increased likelihood of systems compromise

IoT Systems often fall into the unplanned, under-managed category

Several aspects of IoT Systems deployments can contribute to them having high risk of being weakly planned and under-managed systems —

- lack of precedent for implementation & management

- cities/institutions don’t have deep experience with these systems

- true for all phases – systems selection, procurement, implementation, & management

- few, if any, peer cities/institutions from which to learn for systems expected to last years or decades (sufficient time hasn’t gone by)

- cities/institutions don’t have deep experience with these systems

- accountability and ownership unclear

- IoT systems span many organizations within a city or institution

- most organizations are not familiar or practiced at coordinating with each other in this role

- acquisition path – IoT Systems can come into the institution through many non-traditional paths

- these IoT Systems are rarely acquired by central IT

- even if acquired through central IT, traditional systems vetting approaches not sufficient

- no established vetting of IoT systems prior to purchase

- performance expectations unknown or unclear (see ownership above)

- the city or institutional department acquiring the system might not be the one supporting the system

- Newness and rapid evolution IoT Systems makes them hard to discuss, categorize, and plan for

the newness, novelty, and rapid evolution of IoT Systems will continue to make very susceptible to being under-managed systems

Rapid evolution of IoT Systems vs glacial pace of institutional change

While there are no silver bullets or magic technologies (and we shouldn’t spend much time looking for them) to address these added risks that IoT Systems bring, there are things that we can do now, or at least begin now, that can positively impact our risk exposure as institutions and cities. While we’re interested in mitigating risks that we have now from IoT Systems, the impact of IoT systems in our cities and institutions in the future will be much higher.

Some things that can be done now include —

- establish a set of criteria for your city’s or institution’s for IoT Systems

- identify IoT Systems ownership and accountability

- require before acquisition

- identify institutional language used to communicate traditional risk & incorporate that into IoT risk conversations, guidelines, and planning

- consider an IoT Systems oversight group for your city or institution

Making broad changes, perception changes, and policy changes in cities and institutions is arduous work that takes time, leadership, political capital, and patience. It is important that we begin now because this level of institutional change will likely take some time and the impact of not making the changes is increasing rapidly.

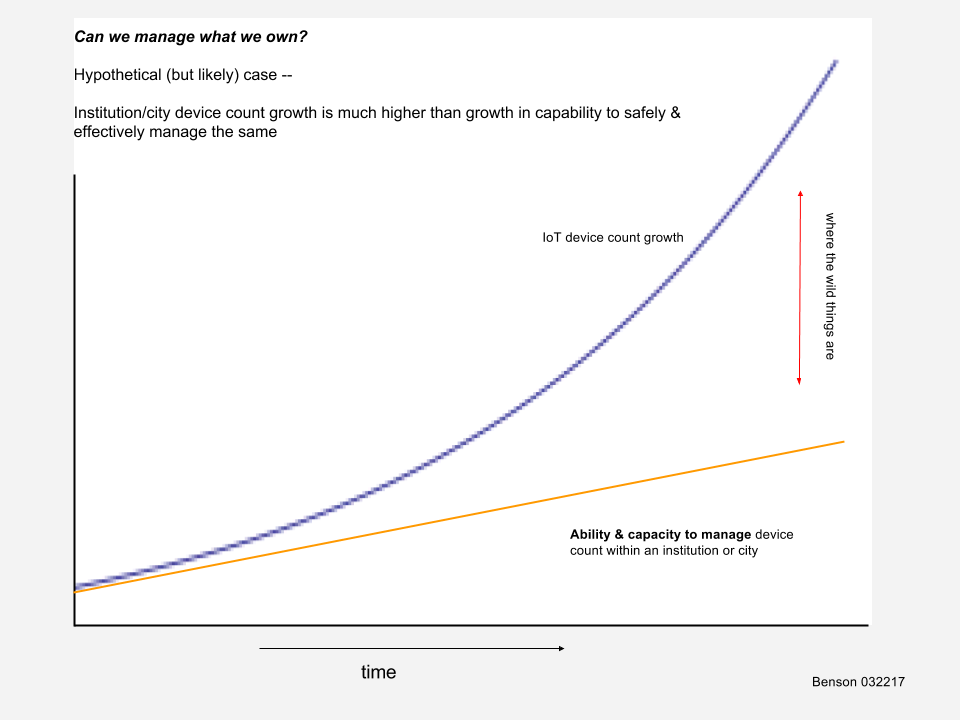

Can we manage what we own? — IoT in smart cities & institutions

The rate of growth of IoT devices and systems is rapidly outpacing the ability of an institution or city to manage those same devices and systems. The tools, capacities, and skill sets in institutions and cities that are currently in place were built and staffed for different information systems and technologies — centralized mail servers, file sharing, business applications, network infrastructure support, and similar. Some of these systems still exist within the enterprise and still need robust, effective support while others have moved to the cloud. The important consideration is to not assume that toolsets developed for traditional enterprise implementations are appropriate or sufficient for IoT Systems implementations.

Working from the outside in

Starting with the outer ring, the number of ‘things’ — the T in IoT — is rapidly growing within institutions and cities. From my perspective, an IoT ‘thing’ is a device that computes in some way, is networked, and interacts with its local environment in some way. Further, these systems may be acquired via non-traditional methods. For example, a city’s transportation department may seek and acquire a sensor, data aggregation, and analysis system for predictive maintenance for a particular roadway. This system might have been selected, procured, implemented, and subsequently managed independently of the organization’s traditional central IT organization & processes. Complex and high data producing systems are entering the institution/city from a variety of sources and with little formal vetting or analysis.

Can we even count them?

Because of the rapid growth of IoT devices and systems in concert with alternative entry points into the city/institution, even counting (enumerating) — these devices — which can compute with growing ability and are networked — is increasingly difficult. This lack of countability in itself is not so bad, it’s just a fact of life – the trouble comes when we base our management systems on the assumption that we can count, inventory, much less manage all of our devices.

What do we know about the devices?

Do we have documentation and clarity of support for the tens, hundreds, thousands (or more) of devices. What do they do? How are they configured? Have we set a standard for configuration? How do we know that that standard is being met? What services do we think should be running on the devices? Are those services indeed running on them? Are there more services than those required running? Are there processes for sampling and auditing those device services over the next 12 – 36 months? Or did we install them, or have them installed, and simply move onto the next thing?

We can borrow from the construction industry and ask for as-built documentation. What actually got installed? What are the documents that we have to work with to support this system? Drawings? IP addresses? Configuration documents for logins, passwords, open ports/services?

What is manageable?

If we are in the fortunate position to be able to actually count these computing/networked/sensing devices with reasonable accuracy and we know some (enough) things about the devices, then the next question is — do we have the resources — staffing, time, skill sets, opportunity cost, etc — to actually support the devices? Suddenly in smart cities, smart institutions, smart campuses, we’re installing things, endpoints, in the field that may require regular updating (yearly, monthly, …) — and this occurs between the customer network with its protocols/processes and the vendor system that is proposed. Not all (possibly substantial) device updating can be accomplished effectively remotely.

Another challenge is that often the organizations that are charged with staffing, installing, and supporting these deployed IoT devices, such as smart energy meters or environmental monitoring systems, are more accustomed to supporting machines that last for years or decades. Such facilities management organizations have naturally built their planning, repair, and preventative maintenance cycles around longer periods. For example, a centrifugal fan in a building might have a projected lifespan of approximately 25 years, soft start electric motors 25 years, and variable air volume (VAV) boxes with expectancies of 25 years.

Similarly, central IT organizations generally are not accustomed to running out into the field with trucks and ladders to support 100’s, 1000’s, or more of computing, networked devices in a city or institution. So the question of who’s going to do the actual support work in the field is not clear in terms of capacity, skill sets, and costs.

Actually managing the things

So, if we have all of the above — and that subset gets smaller and smaller — have the decisions been made and priorities established to actually manage the devices? That is, to prioritize, risk manage, and develop process to manage the devices in practice? There’s a good chance that manageable things won’t actually be managed due to lack of knowledge of owned things, competing priorities, and other.

On not managing the things

It is my opinion that we will not be able to manage all of the ‘things’ in the manner that we have historically managed networked, computing things. While that’s a change, that’s not all bad either. However we do have to realize, acknowledge, and adjust for the fact that we’re not managing all of these things like we thought we could. Thinking we’re managing something we’re not is the biggest risk.

We’re moving into a world of potentially greater benefit to the populace via technology and information systems. However, we will have to do the hard work of being thoughtful about it across multiple populations and realize that we’re bringing in new risks with some known — and unknown — consequences.