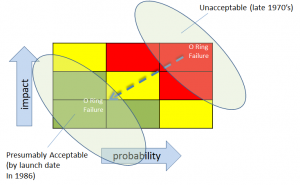

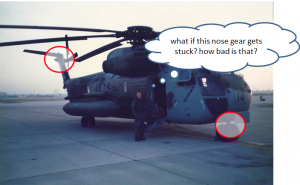

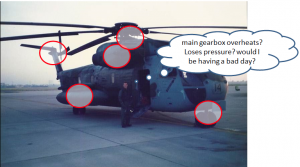

As we manage the online existence of our enterprises, we have discussed that we must rid ourselves of the illusion of total control, certainty, and predictability. Ironically, however, we often must move forward as if we’re certain or near-certain of the outcome. No shortage of irony, contradiction, and paradox here.

While playing horseshoes over Memorial Day Weekend with neighbors, I had a minor epiphany regarding uncertainty. I realized that once I tossed my horseshoe and it landed in the other pit (a shallow three-sided box made up of sand, dirt, some tree roots, and the pin itself) that

I had no idea about where that horseshoe was going to bounce.

I had some control over the initial toss — I could usually get it in the box — but once it hit the ground, I had zero certainty about which direction it was heading. It might bury in the sand, bounce high on the dirt, or hit a tree root and fly off to parts unknown.

Because I couldn’t control that bounce, my best opportunity for winning was to get that horseshoe to land in the immediate vicinity of that pin as often as possible so that I created the opportunity for that arbitrary bounce to land on the pin as often as possible.

By seeking to place that horseshoe near that pin for the first bounce as often as I could, the more likely it was to land on, near, or around the pin for points or even the highly coveted ringer.

Here’s the irony. One of the best ways to achieve this goal of landing the shoe near the pin as often as possible, is to aim for the pin every time. That is, toss the horseshoe like you expect to get a ringer with every throw.

So, we’re simultaneously admitting to ourselves that we can’t control the outcome while proceeding as if we can control the outcome.

This logical incongruity is precisely the sort of thing that can make addressing uncertainty and managing risk so challenging.

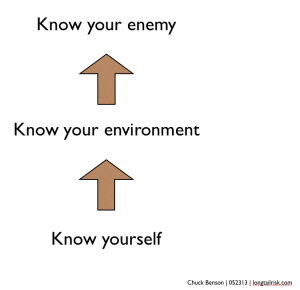

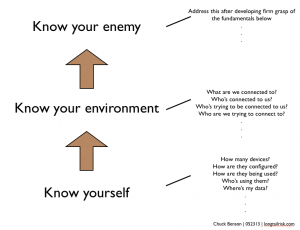

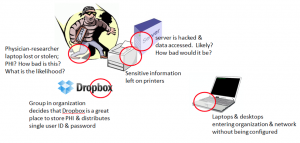

Similar things happen with the management of our information systems. We want to earnestly move forward with objectives like 100% accurate inventory and 100% of devices on a configuration management plan. Most of us know that’s not going to happen in practice with our limited resources. However,

- by choosing good management objectives (historically known as ‘controls’)

- executing earnestly towards those objectives while

- thoughtfully managing resources,

we increase the chances of things going our way even while living in the middle of a world that we ultimately can’t control.

Those enterprises that do this well not only increase survivability, but also increase competitive advantage because they will use resources where they are most needed and not waste them where they don’t add value.

So, yes, I’m trying to get a ringer with every throw, but at the same time, I know that is unlikely. But while shooting for the ringer every time, I increase the opportunity for that arbitrary bounce to go in a way that’s helpful to me.

Much like horseshoes, in Information Risk Management, I can’t control what is going to happen on every single IT asset, be it workstation, server, or router, but I can do things to increase the chances for things move in a helpful way.

The opportunity for growth before us, then, is to have that self-awareness of genuinely moving towards a goal, simultaneously knowing that it is unlikely that we will reach it, and being ready to adjust when and if we don’t.

How do you create opportunity for taking advantage of uncertainty in your organization?