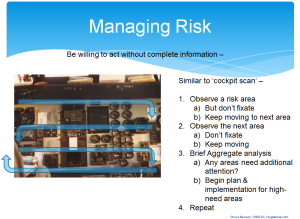

Cockpit Scan

Learning to scan is one of the most important skills any pilot develops when learning to fly. In flying, scan is the act of keeping your eyes moving in a methodical, systematic, and smooth way so that you take in information as efficiently as possible, while leaving yourself mental bandwidth for processing that information.

While flying the aircraft, as you look out across the horizon, your scan might start near the left of the horizon and scan across to the right. Then, upon approaching the right of the horizon, you drop your eyes down a little bit and start scanning back right to left and pick up some instrument readings along the way. As you approach the left side, you might drop your eyes a little again, change directions, scanning left to right again. You might repeat this one more time and then finally return back to where you started. Then do it again.

The exact pattern doesn’t matter, but having a pattern and method does.

At first, this is all easier said than done. When you’re learning to fly, so much is uncertain. You really don’t know much. You want to lower your uncertainty. There is a real tendency to want to know everything about everything. But you’ll never know everything about everything. Slowly, a budding pilot begins to learn that.

When I was learning to fly and while mistakenly trying to know every detail about every flight parameter, ironically I would end up (unhelpfully) having what I now call my “instrument of the day”. I would get so focused on one thing, say the engine power setting, that I would disregard most of everything else. (This is why there are instructor pilots.) On the subsequent flight, the instrument might have been the altimeter where I’d be thinking, “By God, I’m going to hold 3,000 feet no matter what! I’m going to own this altitude!” Now the fact that I wasn’t watching anything else and we may have been slowing to stall speed was lost on me because I was so intent on complete knowledge of that one indicator or flight parameter. (This is why there are instructor pilots.)

To develop an effective scan, you slowly learn that you can’t know everything. You learn that you have to work with partial information.

You have to live with uncertainty in order to fly.

By accepting partial information about many things and then slowly integrating that information through repetitive, ongoing scans, you gain what you need to fly competently and safely. Conversely, if you focus solely on one or two parameters and really ‘know’ them, you’ve given up your ability to have some knowledge on the other things that you need to fly. In my example above with engine power setting, I could ‘know’ the heck out of what that power setting was, but that told me nothing about my airspeed, altitude, turn rate, etc. It doesn’t even tell me if I’m right side up. While we can’t know everything about everything, we do want to know a little bit about a lot of things.

“Scan” even becomes a noun. “Develop your scan.” “Get back to your scan.” “Don’t let your scan break down.”

Your flying becomes better as your scan becomes better.

After a while, that scan becomes second nature. As a pilot gains in experience, the trick then becomes to keep your scan moving even when something interesting is happening, eg some indicator is starting to look abnormal (and you might be starting to get a little nervous). You still want to keep your scan moving and not fixate on any one parameter —

Just because something bad is happening in one place does not mean that something bad (or worse) is not happening somewhere else.

The pilot’s scan objectives are:

- Continually scan

- Don’t get overly distracted when anomalies/potential problems appear — keep your scan moving

- Don’t fixate on any one parameter — force yourself to work with partial information on that parameter so that you have bandwidth to collect & integrate information from other parameters and other resources

- If disrupting your scan is unavoidable, return to your scan as soon as possible

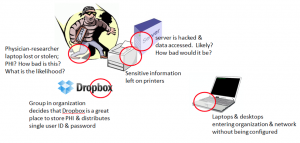

Maintaining Your Scan In Information Risk Management

This applies to Information Risk Management as well. We want to continually review our information system health, status, and indicators. If an indicator starts to appear abnormal, we want to take note but continue our scan. Again, just because an indicator appears abnormal doesn’t preclude there being a problem, possibly bigger, somewhere else.

A great example is the recent rise in two-pronged information attacks against industry and government. Increasingly, sophisticated hackers are using an initial attack as a diversion and then launching a secondary attack while a company’s resources are distracted by the first attack. A recent example of this sort of approach is when the Dutch bank, ING Group, had their online services disrupted by hackers and then followed with a phishing attack on ING banking customers.

This one-two punch is also an approach that we have seen terrorists use over the years where an initial bomb explosion is followed by a second bomb explosion in an attempt to target first-responders.

(As an aside, we know Boston Marathon-related phishing emails were received within minutes of news of the explosions. I don’t know whether this was automated or manual phishing attacks, but either way, someone was waiting for disasters or other big news events to exploit or leverage.)

I believe that we will continue to see more of these combination attacks. Further, it is likely that not just one, but rather multiple, incidents will serve as distractions while the real damage is being done elsewhere.

To address this, we must continue to develop and hone our scan skills. We must:

- Develop the maturity and confidence to operate with partial information

- Practice our scan, our methodical and continual monitoring, so that it becomes second nature to us

- Have the presence of mind and resilience to return to our scan if disrupted

Do you regularly review your risk posture? What techniques do you deploy in your scan? What are your indicators of a successful scan?