Winston Churchill 1942

Winston Churchill is frequently quoted as saying, ‘Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the other ones.’ I feel a similar thing might be said about risk management: ‘Risk management is the worst form of predictive analysis for making IT, Information Management, and cybersecurity decisions, except for all the other ones.’

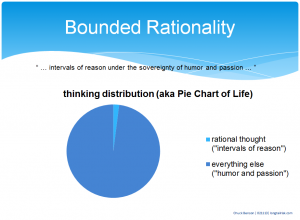

Because there is so much complexity and so many factors and systems to consider in IT, Information Management, and cybersecurity, we resort to risk management as a technique to help us make decisions. As we consider options and problem-solve, we can’t logically follow every possible approach and solution through and analyze each one on its relative merits. There are simply way too many. So we try to group things into buckets of like types and analyze them very generally with estimated likelihoods and estimated impacts.

We resort to risk management methods, because we know so little about the merits of future options that we have to ‘resort to’ this guessing game. That said, it’s the best game in town. We have to remind ourselves that the reason that we are doing risk management to begin with is that we know so little.

In some ways, it is a system of reasoned guesses — we take our best stabs at the likelihood of events and what we think the impacts of events might be. We accept the imprecision and approximations of risk management because we have no other better alternatives.

Approximate approximations

It gets worse. In the practice of managing IT and cybersecurity risk, we find that we have trouble doing the things that allow us to make those approximations that are to guide us. Our approximations are approximations.

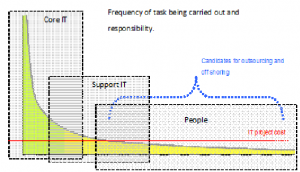

Managing risk is about establishing fractions. In theory we establish the domain over which we intend to manage risk, much like a denominator, and we consider various subsets of that domain as we group things into buckets for simpler analysis, the numerator. The denominator might be all of the possible events in a particular domain, or it might be all of the pieces of equipment upon which we want to reflect, or maybe it’s all of the users or another measure.

When we manage risk, we want to do something like this:

- Identify the stuff, the domain — what’s the scope of things that we’re concerned about? How many things are we talking about? Where are these things? Count these things

- Figure out how we want to quantify the risk of that stuff — how do we figure out the likelihood of an event, how do we want to quantify the impact?

- Do that work — quantify it, prioritize it

- Come up with a plan for mitigating the risks that we’ve identified, quantified, & prioritized

- Execute that mitigation (do that work)

- Measure the outcome (we did some work to make things less bad; we’re we successful at making things less bad?)

The problem is that in this realm of increasingly complex problems, the 1st step, the one in which we establish the denominator, doesn’t get done. We’re having a heck of a time with #1 — identifying and counting the stuff — and this is supposed to be the easy step. Often we’re surprised by this. In fact, sometimes we don’t even realize that we’re failing at step #1 — because it’s supposed to be the easy part of the process. However, the effects of BYOD, hundreds of new SaaS services that don’t require substantial capital investment, regular fluctuations in users, evolving and unclear organizational hierarchies, and other factors all contribute to this inability to establish the denominator. A robust denominator, one that fully establishes our domain, is missing.

Solar flares and cyberattacks

Unlike industries such as finance, shipping, and some health sectors, which can have sometimes hundreds of years of data to analyze, the IT, Information Management, and cybersecurity industries are very new and are evolving very rapidly. There is not the option of substantial historical data to assist with predictive analysis.

Unlike industries such as finance, shipping, and some health sectors, which can have sometimes hundreds of years of data to analyze, the IT, Information Management, and cybersecurity industries are very new and are evolving very rapidly. There is not the option of substantial historical data to assist with predictive analysis.

However, even firms such as Lloyd’s of London must deal with emerging risk for which there is little to no historical data. Speaking on attempting to underwrite risks from solar flare damages (of all things), emerging risks manager, Neil Smith says, “In the future types of cover may be developed but the challenge is the size of the risk and getting suitable data to be able to quantify it … The challenge for underwriters of any new risk is being able to quantify and price the risk. This typically requires loss data, but for new risks that doesn’t really exist.” While this is talking about analyzing solar flare risk, it can be readily applied to risk we have in cybersecurity and Information Management.

In an interview with Lloyds.com, reinsurer Swiss Re Corporate Solutions head of global markets, Oliver Dlugosch, says that he takes the following steps when evaluating an emerging risk:

- Is the risk insurable?

- Does the company have the risk appetite for this particular emerging risk?

- Can the risk be quantified (particularly in the absence of large amounts of historical data)?

Whence the denominator?

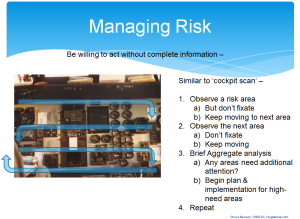

So back to the missing denominator. What to do? How do we do our risk analysis? Some options for addressing this missing denominator might be:

- Go no further until that denominator is established. (However, that is not likely to be fruitful as we may never get to do any analysis if we get hung up on step 1) OR

- Make the problem space very small so that we have a tractable denominator (but then our risk analysis is probably so narrow that it is not useful to us) OR

- Move forward with only a partial denominator and being ready to continually backfill that denominator as we learn more about our evolving environment.

I think there is something to approach #3. The downside is that with it we may feel we are departing what we perceive as intellectual honesty, scientific method, or possibly even ‘truthiness.’ However, it is better than #1 or 2 and better than doing nothing. I think we can resolve the intellectual honesty part to ourselves by 1) acknowledging that this approach will take more work (ie constantly updating the quantity and quality of the denominator) and 2) acknowledging that we’re going to know even less than we were hoping for.

So, more work to know less than we were hoping for. It doesn’t sound very appetizing, but as the world becomes increasingly complex, I think we have to accept that we will know less about the future and that this approach is our best shot.

“Not everything that can be counted counts. Not everything that counts can be counted.”

William Bruce Cameron (probably)

[Images: WikiMedia Commons]