The transcript of the hearing on “China, the United States, and Next Generation Connectivity” before the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, addressing IoT and 5G technologies, came out this week and is available here. My testimony is early in the document. See earlier post for overview.

Tag Archives: security

FTC IoT guideline describes complexity, nuance of IoT

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has issued a guideline to companies developing Internet of Things (IoT) products and services. The guideline addresses security, privacy, encryption, authentication, permission control, testing, default settings, patch/software update planning, customer communication and education, and others.

IoT irony

The irony is that the comprehensiveness of the document, the things to plan for and look out for when developing IoT devices and systems, is the same thing that makes me think that the preponderance of device manufacturers will never do most of the things suggested. At least not in the near term. Big companies that have established brand, (eg Microsoft, Cisco, Intel, others) will have the motivation (and capacity) to participate in most of these recommendations. However, the bulk of the companies and likely the bulk of the total IoT device/system marketplace entries will be from the long tail of companies and businesses.

These companies are the smaller companies and startups that are just trying to get into the game. They won’t have an established brand across a large consumer base. This can also be read as, ‘they don’t have as much to lose’. Their risk and resource allocation picture does not include an established brand that needs to protected. They don’t have a brand yet. For most of these startup and small companies, they will view their better play to be:

- throw our cool idea out there

- get something on the market

- if we get a toehold & start to establish some brand, then we’ll start to worry about being more comprehensive with the FTC suggestions

Change

Again, to be clear, I am appreciative of the FTC guideline for manufacturers and developers of Internet of Things devices. It’s a needed document and is thoughtful, well-written, and thorough. However, the same document can’t help but illustrate all of the variables and complexities of networked computing regarding privacy and security concerns — the same privacy and security concerns that most companies will have insufficient resources and motivation to address.

We’re in for a change. It’s way more complicated than just ‘bad or good’. Where we help protect and manage risk for our organizations, we’re going to have to change how we approach things in our risk management and security efforts. No one else is going to do it for us.

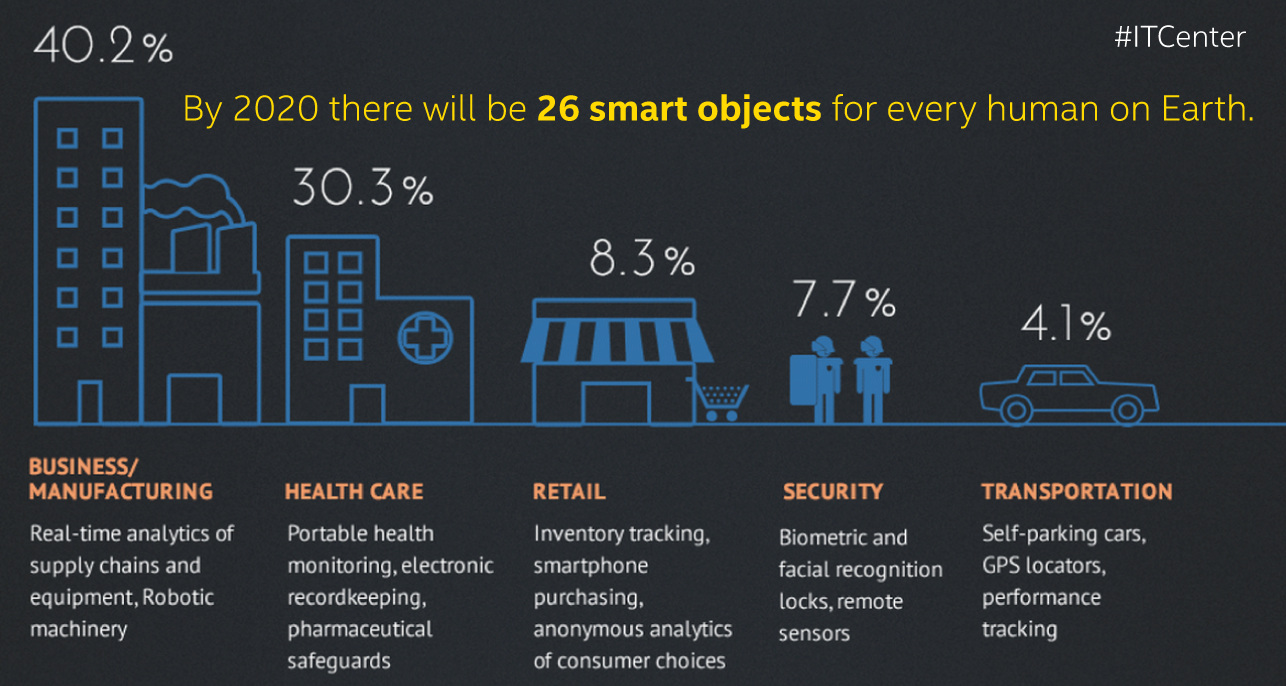

IoT – Lots of addressable things …

Compliance excesses

Probably one of the earliest papers written on control theory was James Clerk Maxwell’s, On Governors, published in 1868. In the paper, Maxwell documented the observation that too much control can have the opposite of the desired effect.

Compliance efforts, in general, and certainly in cybersecurity work, can be seen as a governing activity. The idea is that, without compliance activity, a business or government enterprise would have one or many components that operate to excess. This excess might manifest itself in financial loss, personal injury, damage to property, breaking laws, or otherwise creating (most likely unseen) risk to the customer base or citizenry. For example, a company that manages personally identifiable information as a part of its service has an obligation to take care of that data.

In moderation, regulatory compliance makes sense. Some mandated regulatory activities can build in a desirable safety cushion and lower risk to customers and citizens. The problem, of course, is what defines moderation?.

Compliance and regulatory rules are generally additive. One doesn’t often hear that an update to a regulation is going to remove rules, constraints, or restrictions. Updated regulatory law far more often adds regulation. More to do. More to do usually means more time, effort, and resources that have to come from somewhere if an organization is indeed to ‘be compliant’.

Tightening the screws

Maxwell was a savant, making far-reaching contributions to math and the science of electromagnetism, electricity, and optics, and dying by the age of 48. Einstein described Maxwell’s work as “the most profound and the most fruitful that physics has experienced since the time of Newton.”

In his paper, On Governors, Maxwell wrote,

“If, by altering the adjustments of the machine, its governing power is continually increased, there is generally a limit at which the disturbance, instead of subsiding more rapidly, becomes an oscillating and jerking motion, increasing in violence till it reaches the limit of action of the governor.”

Maxwell’s observation of physical governors creating the opposite of intended behavior once a certain point of additional control has been added has other parallels in the natural world such as overcoached sports teams, overproduced record albums (showing my age here), or micromanaged business or military units. I believe there is also similar application of over-control in the world of compliance.

Often a system with no regulation operates inefficiently or creates often unseen risk to operators and bystanders. Adding a little bit of regulation can allow the system to run more smoothly, lower risk to those around or involved in the system, and allow the system to have a longer life. However, there is a point reached while adding more regulation where detrimental or even self-destructive effects can occur. In Maxwell’s example, the machine would “become an oscillating and jerking motion, increasing in violence” until the physical governor could no longer govern.

That critical zone of too many compliance mandates in business and government systems manifest themselves in undesirable behavior in a couple of ways. One is that the resources to comply with the additional regulations are simply not there. That is, not everything can be complied with if the business is to stay in business or the government process is to continue to function. That means that choices must then be made on what gets complied with. And that means that the entity that is supposedly being regulated is now, by necessity, making its own decisions — independent of regulators, whether directly or indirectly — on what it will comply with and what it will not comply with. That, in itself, is not providing particularly helpful control. Worse, the organization might choose not to do those early compliance rules that were actually helpful.

Another way that too much compliance can have unintended consequences on the system is that if the organization does actually try to comply with everything, redirecting as much of its operating resources as necessary, can in fact bleed itself out. It might go broke trying to comply.

This is not to say that some entities should be allowed to be in business if they don’t have a business model that allows them to support essential regulation. Again, there is some core level of regulation and compliance that serve the common good. However, there is a crossable point where innovation and new opportunity start to wash out because potentially innovative companies, that might add value to the greater good, cannot stay in the game.

“I used to do a little, but a little wouldn’t do it, so a little got more and more”

Axl, Izzy, Slash, Duff, & Steve on Mr. Brownstone from the album Appetite for Destruction, Guns N Roses

The line above, from the Guns N Roses song, Mr. Brownstone, comes to my mind sometimes when thinking about compliance excess, tongue in cheek or not. The song is a dark, frank, (and loud) reflection on addiction. The idea is that a little of something provided some short-term benefit, but then that little something wasn’t enough. That little something needed to be more and more and quickly became a process unto itself. Of course, I’m not saying that excessive compliance = heroin addiction, but both do illustrate systems gone awry.

So where is the stopping point for compliance, particularly in cybersecurity? When does that amount of regulatory activity, that previously was helpful, start to become too much?

I don’t know. And worse, there’s no great mechanism to determine that for all businesses and governments in all situations. However, I do believe that independent small and medium-sized businesses can make good or at least reasonable decisions for themselves as well as the greater good for the community. I would suggest:

- determine how much we can contribute to our respective compliance efforts

- prioritize our security compliance efforts

- start with compliance items that allow us to balance what 1) makes us most secure, 2) contributes most to the security of the online community, and 3) (save ourselves here) could have the stiffest penalties for noncompliance

- Know what things that we are not complying with. Even if we can’t comply with everything, we still have to know what the law is. Have a plan, even if brief, for addressing the things that we currently can’t comply with. Even though the regulatory and compliance environment is complicated, it’s not okay to throw up our hands and pretend it’s not there.

I believe that the nature of our system in the US is to become increasingly regulatory, that is additive, and more taxing to comply with. However, we still need to know what the rules are and what the law is. From there, I believe, what defines the leadership and character of the small to medium size business or government entity is the choices that we make for ourselves and the greater good of the community.

[Governor & Maxwell Images: WikiMedia]

[Rolling Stone cover image: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/pictures/gallery-the-best-break-out-bands-on-rolling-stones-cover-20110502/guns-n-roses-1988-0641642]

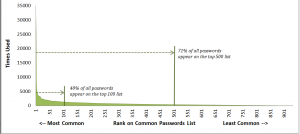

Password usage seems to follow Zipf distribution

Like word distributions and company sizes, frequency of usage of particular passwords seems to follow a Zipf distribution or power law distribution. That is, there are a lot of people that pick from a small common pool of passwords and that the number of people that use a particular password drops off quickly once you step away from that common pool.

Mark Burnett’s research shows that, of a list of 10,000 ranked passwords:

Mark Burnett’s research shows that, of a list of 10,000 ranked passwords:

- 91% of users have a password from the top 1000 passwords

- 79% of users have a password from the top 500 passwords

- 40% of users have a password from the top 100 passwords

BTW, almost 5% of all users have the password, ‘password’.

List of top passwords here. Heads up — there’s some colorful language in play here for popular passwords.

Most SMB’s don’t consider cyberattack a substantial risk to their business

Ponemon Institute has released its Risk of an Uncertain Security Strategy study. It surveyed over 2000 IT professionals overseeing the security role in their respective organizations. The study identified 7 consequent risks of uncertainty in security strategy:

1. Cyber attacks go undetected

2. Data breach root causes are not determined

3. Intelligence to stop exploits is not actionable

4. Cybersecurity is not a priority

5. Weak business case for investing in cyber security

6. Mobility and BYOD security ambiguity

7. Financial impact of cyber crime is unknown

Most respondents believe that compliance efforts did not enhance security posture: [Do you agree that] “compliance standards do not lead to a stronger security posture?”

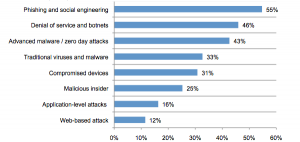

Types of attacks that respondents reported are summarized as:

Notably, 31% of respondents said that no one person or role was in charge of establishing security priorities. 58% said that management does not see cybersecurity as a significant risk. Finally, the study also indicated that the further up one went in the organization’s hierarchy, the more distant they were from understanding the organization’s cyber risk and related strategy. While not surprising, this is discouraging.

I keep getting back to the idea of force protection that the military had to develop 30 years ago. In response to world events to include attacks on bases and personnel, the military realized that it needed to explicitly remove resources, funds, and capacity off of the operational (pointy) end and use them to protect and resource the rear if they were to be survivable and sustainable. Over time, I think the market will bear this out too for most SMB’s. That is, I believe that those businesses that have been successful over several years will tend to be the ones that have made some investment in cybersecurity and resilience. And of the businesses that disappear after a short time, a high correlation will be made with those that did not invest in resilience.

Even though these conclusions might be fairly obvious, it’s not going to be pretty to watch.

SMB’s operating under false sense of security

When I used to fly in the service, one of the safety concerns was ‘complacency’. Complacency was letting down your guard because of a feeling of safety based on numerous previous flights where nothing bad had happened. System X never failed, system Y hadn’t failed, system Z had failed a little bit, but there was a backup, etc. Per a recent McAfee and Office Depot survey, small to medium sized businesses (SMB’s) are suffering from a similar thing.

From a study of over 1000 participants, a majority (66%) felt confident that their devices and data were safe from hackers. Further, 77% felt they had never been hacked. This feeling of security is inconsistent with the evidence of SMB’s increasingly being targets of cyber attacks. According to a statement by Congressman Chris Collins, part of the reason for this complacency is that attacks on small and medium sized businesses typically don’t make the news. However there are a lot of them, hence the long tail. According to McAfee, another reason for the increasing malicious activity on SMB’s is that larger businesses have had some success in hardening their enterprises to cyberattack and that has shifted the effort-invested and payoff balance for cyber criminals.

The study also found that 45% of the SMB’s responding did not secure data on employee’s personal devices and 14% hadn’t implemented any security measures at all.

Lots of dots

Per this article: http://bit.ly/1gJA0yu at Tofino and Bob Radvanovsky:

- over 1,000,000 ICS/SCADA devices connected to the Internet discovered so far

- discovering approximately 5,000 new ICS/SCADA connected devices/day

Device types include, but not limited to:

- manufacturing/production control systems

- medical devices

- traffic management systems

- traffic light control/traffic cameras

- HVAC & building management systems

- security/access control to include video/audio surveillance

- data radios

and to keep it interesting, also found these connected to the Internet:

- off-road mining trucks

- crematoriums

In many cases, a web interface is enabled with default credentials in place.

I believe 1,000,000 is only a fraction of Internet-connected embedded/ICS/SCADA devices and that the rate of growth of new connections is way faster than anything that we saw in the PC days.

Who’s looking at you kid? — ICS in the office

The “Internet of Things” is slowly creeping into small businesses and homes and is creating some new privacy and physical safety issues and risks.

There has been a lot of media coverage regarding exposure of the national power grid to cyberattack. This coverage is appropriate and the risk is real. Many automated systems, aka industrial control systems or ICS, that control various aspects of electricity generation, transmission, and distribution were never intended to be controlled by Internet-connected systems. In most cases the Internet simply did not exist when the systems were installed. However, Internet-based control was added after the fact and the intersection (or collision) of two very different types of control systems — traditional industrial control and Internet-based control has created vulnerability and exposure to malicious intent. The issue is exacerbated by the fact that power systems are a high value target — successful attack and compromise can have a very big effect.

There has been a lot of media coverage regarding exposure of the national power grid to cyberattack. This coverage is appropriate and the risk is real. Many automated systems, aka industrial control systems or ICS, that control various aspects of electricity generation, transmission, and distribution were never intended to be controlled by Internet-connected systems. In most cases the Internet simply did not exist when the systems were installed. However, Internet-based control was added after the fact and the intersection (or collision) of two very different types of control systems — traditional industrial control and Internet-based control has created vulnerability and exposure to malicious intent. The issue is exacerbated by the fact that power systems are a high value target — successful attack and compromise can have a very big effect.

There are also other control systems, besides those dealing with power, that are in many buildings and increasingly in homes and small offices. These are HVAC (heating ventilation air conditioning) controls, lighting controls, security systems and others. These also have various levels of exposure to cyber attack. As an example, Google’s headquarters in Australia was recently compromised.

ICS showing up in home and office & unintended consequences

Some of these control systems that have traditionally been the domain of large buildings and complexes are making their way into homes and offices.

One example is IP-based (Internet controlled) consumer or small business security systems. These systems often provide:

- video monitoring over network/Internet

- audio monitoring over network/Internet

- sometimes 2-way audio over Internet where the person monitoring can send audio transmissions to the monitored area

These devices are inexpensive and easily obtained at Target, Best Buy, Radio Shack or even the local drug store. They are also very vulnerable to misuse over the Internet. There was a well-publicized case last month where an IP-based (Internet-controlled) baby monitor was being used by a family in Texas. When the parents thought they heard a voice in the 2 year old child’s room, they heard a man’s voice saying horrible things to the child through the baby monitor (to include calling her by name). Someone had ‘hacked’ into the system (‘hack’ is a strong word as it was almost trivial to gain video and audio access).

These devices are inexpensive and easily obtained at Target, Best Buy, Radio Shack or even the local drug store. They are also very vulnerable to misuse over the Internet. There was a well-publicized case last month where an IP-based (Internet-controlled) baby monitor was being used by a family in Texas. When the parents thought they heard a voice in the 2 year old child’s room, they heard a man’s voice saying horrible things to the child through the baby monitor (to include calling her by name). Someone had ‘hacked’ into the system (‘hack’ is a strong word as it was almost trivial to gain video and audio access).

The parents thought that they were enhancing the child’s safety and well-being and had no idea that they were increasing risk to the child in other ways.

Assumed product sanction

There’s the rub. When these products are purchased at our local or online stores, there is this assumption of some sort of sanctioning or trust of the product by the store. Sort of like, “Target wouldn’t sell anything that would hurt me. Best Buy knows what they are selling.” This is, of course, a bad assumption.

The Internet of Things — devices and sensors talking to each other as well as humans over the Internet — opens up an exciting array of possibilities. But simultaneously it opens up a new ecosystem for misuse, privacy abuse, and even physical safety issues.

When we bring Internet-controlled devices into our office or home environments, we need to do the mental math of how the product could be misused. What would happen if it failed? What would happen if (when) an unplanned user accesses the system? Because we can be sure that someone else, that may not be well-aligned with our best interests, is doing that math.

photo credit: Argonne National Laboratory via photopin cc

Motivating adoption of cybersecurity frameworks

The Federal government is seeking to motivate businesses that operate our nation’s critical infrastructure systems to voluntarily adopt a Cybersecurity Framework currently under development by NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). These systems include the electricity generation and distribution grid, transportation systems, and drinking water storage and distribution systems. A preliminary draft is available now here and it will also be presented in two weeks at the University of Texas.

The Federal government is seeking to motivate businesses that operate our nation’s critical infrastructure systems to voluntarily adopt a Cybersecurity Framework currently under development by NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). These systems include the electricity generation and distribution grid, transportation systems, and drinking water storage and distribution systems. A preliminary draft is available now here and it will also be presented in two weeks at the University of Texas.

Roughly simultaneously, the Departments of Homeland Security, Treasury, and Commerce have been developing various options to try to provide incentives for companies to voluntarily adopt the Framework. Per the White House Blog, there are eight core areas or approaches to incentives under consideration.

- Engage the insurance industry to develop a robust cybersecurity insurance market. As discussed in an earlier post, this is not without it’s challenges.

- Require adoption of the Framework for consideration of Federal grants related to critical infrastructure or include as a weighted criteria as a part of the grant evaluation process. This seems reasonable to me, though it only incentivizes those companies applying for Federal grants (but maybe that’s most companies?)

- Expedite government service provision for various programs based upon adoption of the voluntary Framework adoption. Again, seems logical, though this one seems a short step away from changing the ‘voluntary’ part of the Framework adoption.

- Somehow reduce liability exposure of companies that adopt the Framework. Per the White House Blog, this could include reduced tort liability, limited indemnity, higher burdens of proof, and/or the creation of Federal legal privilege that preempts State disclosure requirements. If one were a cynic, that last one could sound like buying a loop hole. This whole core area of modifying liability seems to be to be pretty tough to manage, particularly to manage transparently and equitably.

- The White House Blog says that “Streamlining Regulations” would be another motivator for participating companies. I don’t get this one. I don’t understand how the government could “streamline regulations” for one company but not for another. Sounds to me like interpret the law one way for one company and another way for another company.

- Provide optional public recognition for participating companies. This one seems like a good idea. Sort of a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval, Better Business Bureau endorsement, or similar to Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations endorsement for hospitals.

- Companies in regulated industries such as utilities could be offered some sort of rate recovery contingent upon adoption. This seems reasonable logically, but I would imagine a bear to implement and manage (which is kind of a theme for many of these).

- The White House Blog says that “cybersecurity research” is an incentive. This one I don’t get either. How does identifying weak spots in the Framework and encouraging research in those weak areas motivate Framework adoption? I mean it’s a good thing to do, but how does that make any one particular company want to participate.

While these are proposals for incentives for critical infrastructure companies, I’m wondering if some of these can serve as a model for SMB’s for adoption of cybersecurity standards for SMBs. Adjusting cyber insurance premiums based on participation would seem to be an obvious approach. However, as has been discussed previously, a mature cyber insurance market does not yet exist and it’s not a slam dunk that one will evolve sufficiently fast to address this need. For SMB’s seeking government grants, to include SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) grants, compliance with an SMB cybersecurity framework would seem to be a no brainer. Also, optional public recognition for compliance with an SMB cybersecurity framework would seem to be a practical approach.

What would motivate you as an SMB to adopt an established Framework?