via krebsonsecurity.com

via krebsonsecurity.com

The “Internet of Things” is slowly creeping into small businesses and homes and is creating some new privacy and physical safety issues and risks.

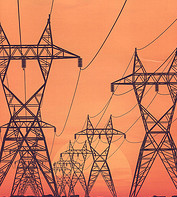

There has been a lot of media coverage regarding exposure of the national power grid to cyberattack. This coverage is appropriate and the risk is real. Many automated systems, aka industrial control systems or ICS, that control various aspects of electricity generation, transmission, and distribution were never intended to be controlled by Internet-connected systems. In most cases the Internet simply did not exist when the systems were installed. However, Internet-based control was added after the fact and the intersection (or collision) of two very different types of control systems — traditional industrial control and Internet-based control has created vulnerability and exposure to malicious intent. The issue is exacerbated by the fact that power systems are a high value target — successful attack and compromise can have a very big effect.

There has been a lot of media coverage regarding exposure of the national power grid to cyberattack. This coverage is appropriate and the risk is real. Many automated systems, aka industrial control systems or ICS, that control various aspects of electricity generation, transmission, and distribution were never intended to be controlled by Internet-connected systems. In most cases the Internet simply did not exist when the systems were installed. However, Internet-based control was added after the fact and the intersection (or collision) of two very different types of control systems — traditional industrial control and Internet-based control has created vulnerability and exposure to malicious intent. The issue is exacerbated by the fact that power systems are a high value target — successful attack and compromise can have a very big effect.

There are also other control systems, besides those dealing with power, that are in many buildings and increasingly in homes and small offices. These are HVAC (heating ventilation air conditioning) controls, lighting controls, security systems and others. These also have various levels of exposure to cyber attack. As an example, Google’s headquarters in Australia was recently compromised.

Some of these control systems that have traditionally been the domain of large buildings and complexes are making their way into homes and offices.

One example is IP-based (Internet controlled) consumer or small business security systems. These systems often provide:

These devices are inexpensive and easily obtained at Target, Best Buy, Radio Shack or even the local drug store. They are also very vulnerable to misuse over the Internet. There was a well-publicized case last month where an IP-based (Internet-controlled) baby monitor was being used by a family in Texas. When the parents thought they heard a voice in the 2 year old child’s room, they heard a man’s voice saying horrible things to the child through the baby monitor (to include calling her by name). Someone had ‘hacked’ into the system (‘hack’ is a strong word as it was almost trivial to gain video and audio access).

These devices are inexpensive and easily obtained at Target, Best Buy, Radio Shack or even the local drug store. They are also very vulnerable to misuse over the Internet. There was a well-publicized case last month where an IP-based (Internet-controlled) baby monitor was being used by a family in Texas. When the parents thought they heard a voice in the 2 year old child’s room, they heard a man’s voice saying horrible things to the child through the baby monitor (to include calling her by name). Someone had ‘hacked’ into the system (‘hack’ is a strong word as it was almost trivial to gain video and audio access).

The parents thought that they were enhancing the child’s safety and well-being and had no idea that they were increasing risk to the child in other ways.

There’s the rub. When these products are purchased at our local or online stores, there is this assumption of some sort of sanctioning or trust of the product by the store. Sort of like, “Target wouldn’t sell anything that would hurt me. Best Buy knows what they are selling.” This is, of course, a bad assumption.

The Internet of Things — devices and sensors talking to each other as well as humans over the Internet — opens up an exciting array of possibilities. But simultaneously it opens up a new ecosystem for misuse, privacy abuse, and even physical safety issues.

When we bring Internet-controlled devices into our office or home environments, we need to do the mental math of how the product could be misused. What would happen if it failed? What would happen if (when) an unplanned user accesses the system? Because we can be sure that someone else, that may not be well-aligned with our best interests, is doing that math.

photo credit: Argonne National Laboratory via photopin cc

The Federal government is seeking to motivate businesses that operate our nation’s critical infrastructure systems to voluntarily adopt a Cybersecurity Framework currently under development by NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). These systems include the electricity generation and distribution grid, transportation systems, and drinking water storage and distribution systems. A preliminary draft is available now here and it will also be presented in two weeks at the University of Texas.

The Federal government is seeking to motivate businesses that operate our nation’s critical infrastructure systems to voluntarily adopt a Cybersecurity Framework currently under development by NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology). These systems include the electricity generation and distribution grid, transportation systems, and drinking water storage and distribution systems. A preliminary draft is available now here and it will also be presented in two weeks at the University of Texas.

Roughly simultaneously, the Departments of Homeland Security, Treasury, and Commerce have been developing various options to try to provide incentives for companies to voluntarily adopt the Framework. Per the White House Blog, there are eight core areas or approaches to incentives under consideration.

While these are proposals for incentives for critical infrastructure companies, I’m wondering if some of these can serve as a model for SMB’s for adoption of cybersecurity standards for SMBs. Adjusting cyber insurance premiums based on participation would seem to be an obvious approach. However, as has been discussed previously, a mature cyber insurance market does not yet exist and it’s not a slam dunk that one will evolve sufficiently fast to address this need. For SMB’s seeking government grants, to include SBIR (Small Business Innovation Research) grants, compliance with an SMB cybersecurity framework would seem to be a no brainer. Also, optional public recognition for compliance with an SMB cybersecurity framework would seem to be a practical approach.

What would motivate you as an SMB to adopt an established Framework?

From this Microsoft blog.

This was an eye opener to me. I would have thought XP infection rates were in the ball park of Windows 7. And this is while XP is still supported!

While there is some obvious self-interest for Microsoft to promote migration from XP, my gut is that this is reasonable data.

What percentage of your computers are still running on XP?

“Cybercrime is no longer an annoyance or another cost of doing business. We are approaching a tipping point where the economic losses generated by cybercrime are threatening to overwhelm the economic benefits created by information technology. Clearly, we need new thinking and approaches to reducing the damage that cybercrime inflicts on the well-being of the world.”

John N. Stewart, Senior Vice President and Chief

Security Officer at Cisco in Cisco 2013 Annual Security Report.

The biggest innovation in targeted attacks by malicious actors in the past year is in what is called Watering Hole Attacks, according to the Symantec Internet Security Threat Report 2013.

The biggest innovation in targeted attacks by malicious actors in the past year is in what is called Watering Hole Attacks, according to the Symantec Internet Security Threat Report 2013.

A Watering Hole Attack is indirect in that instead of attacking the target directly, malicious code is placed on sites that the target is known to visit. According to Threatpost, watering hole attacks have been “used primarily by state-sponsored attackers to spy on rival governments, dissident citizen groups and manufacturing organizations.” Two popular watering hole attacks in the past year have been on the Department of Labor and on the Council of Foreign Relations website. Watering hole attacks have also been used on Facebook, Apple, and Twitter users when malicious code was inserted on a popular iPhone software development site.

Watering hole attacks have multiple phases in their implementation:

One of the reasons that watering hole attacks are effective is that, in many cases, the watering hole website — that has been infected and is waiting to download malicious code — cannot be “blacklisted” because it is a legitimate site and needs to be operational. An example is the Department of Labor site. The site needs to remain available.

The primary activity that SMB’s can do to reduce the risk of watering hole attacks is to keep software current, aka “patched.”. For example, on user computers running Windows, allow Windows to auto update its operating system. Larger companies might have the resources to employ network analysis and detection as well as data analytics to mitigate the watering hole attack. However, as we know, the expertise, staffing, and time for this sort of activity is typically not available to SMB’s.

What work-related (or non-work-related) websites do you or your employees visit?

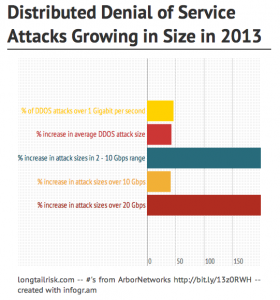

Jeff Wilson with Infonetics Research suggests that attack motivations include:

Jeff Wilson with Infonetics Research suggests that attack motivations include:

Network Computing suggests that reasons for increased attack size stem from:

Developing a market for cybersecurity insurance is more difficult than it may seem. With a rise in business losses stemming from malicious activities and adverse events in the cyber world, creating a market for cybersecurity insurance where losses could be mitigated would seem to be a no brainer. However, developing, maturing, and establishing trust in a cybersecurity insurance market is slow in coming.

Ostensibly, implementation of a mature cybersecurity insurance market can provide protection and mitigation for such events as:

The Department of Homeland Security quotes the Department of Commerce in describing cybersecurity insurance as an “effective, market-driven way of increasing cybersecurity.” The idea is that cybersecurity provides mitigation to damages suffered from a cyber event and also enhances cybersecurity in general by motivating better information risk management and security via premium discounts for good practices.

Despite the seemingly obvious benefits, cybersecurity insurance has yet to undergo wholesale adoption. DHS and the May 2013 Cyber Risk Culture Roundtable Readout Report hosted by the National Protection & Programs Directorate (NPPD) offer some reasons for lack of adoption to date:

At the cybersecurity framework hearing held by the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee on July 25, 2013, Patrick Gallagher, Director of U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) also suggested that the cybersecurity insurance market was not yet sufficiently mature to handle large-scale, catastrophic cyber events. Dr. Gallagher stated that there was not yet a robust actuarial and monetized basis for such large-scale coverage.

Further, at the same hearing, CEO of RSA, Art Coviello suggested that developing an actuarial basis for adverse cyber events was particularly difficult because the computing environment is changing so rapidly and because of the vast amount of data being generated that needs some form of analysis in order to determine appropriate coverage.

As much as I want to encourage and contribute to the rapid development of a mature cybersecurity insurance market, I too have concerns about how policies are written, how cyber events are described, and how much work is required to get an actual payout on a claim. To get consumer buy-in in the short term, insurance providers might have to ‘go long’ with claims and payouts to establish trust and confidence amongst consumers.

Would you purchase cybersecurity insurance? What sorts of events would you like protection from? Data breach? Data loss or theft? What changes/implementations would make purchasing cybersecurity insurance more appealing to you?

[image: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AForgotten_umbrella.jpg]