password alternatives

John Klossner, Dark Reading – http://www.darkreading.com/endpoint/authentication/strong-passwords/d/d-id/1127941

password alternatives

John Klossner, Dark Reading – http://www.darkreading.com/endpoint/authentication/strong-passwords/d/d-id/1127941

Mega-disruptive economic phenomena, or ‘catastronomics’, were the topic of a Centre for Risk Studies seminar at the University of Cambridge last month. Large scale cyberattacks and logic bombs were included with other relatively-unlikely-but-high-impact events like flu pandemics, all out wars between China and Japan, large scale bioterrorism, and other general unpleasantness.

Mega-disruptive economic phenomena, or ‘catastronomics’, were the topic of a Centre for Risk Studies seminar at the University of Cambridge last month. Large scale cyberattacks and logic bombs were included with other relatively-unlikely-but-high-impact events like flu pandemics, all out wars between China and Japan, large scale bioterrorism, and other general unpleasantness.

So, we’ve got that going for us.

[Image: http://supremecourtjester.blogspot.com/2012/12/friday-final-weather-forecast-wear.html]

Probably one of the earliest papers written on control theory was James Clerk Maxwell’s, On Governors, published in 1868. In the paper, Maxwell documented the observation that too much control can have the opposite of the desired effect.

Compliance efforts, in general, and certainly in cybersecurity work, can be seen as a governing activity. The idea is that, without compliance activity, a business or government enterprise would have one or many components that operate to excess. This excess might manifest itself in financial loss, personal injury, damage to property, breaking laws, or otherwise creating (most likely unseen) risk to the customer base or citizenry. For example, a company that manages personally identifiable information as a part of its service has an obligation to take care of that data.

In moderation, regulatory compliance makes sense. Some mandated regulatory activities can build in a desirable safety cushion and lower risk to customers and citizens. The problem, of course, is what defines moderation?.

Compliance and regulatory rules are generally additive. One doesn’t often hear that an update to a regulation is going to remove rules, constraints, or restrictions. Updated regulatory law far more often adds regulation. More to do. More to do usually means more time, effort, and resources that have to come from somewhere if an organization is indeed to ‘be compliant’.

Maxwell was a savant, making far-reaching contributions to math and the science of electromagnetism, electricity, and optics, and dying by the age of 48. Einstein described Maxwell’s work as “the most profound and the most fruitful that physics has experienced since the time of Newton.”

In his paper, On Governors, Maxwell wrote,

“If, by altering the adjustments of the machine, its governing power is continually increased, there is generally a limit at which the disturbance, instead of subsiding more rapidly, becomes an oscillating and jerking motion, increasing in violence till it reaches the limit of action of the governor.”

Maxwell’s observation of physical governors creating the opposite of intended behavior once a certain point of additional control has been added has other parallels in the natural world such as overcoached sports teams, overproduced record albums (showing my age here), or micromanaged business or military units. I believe there is also similar application of over-control in the world of compliance.

Often a system with no regulation operates inefficiently or creates often unseen risk to operators and bystanders. Adding a little bit of regulation can allow the system to run more smoothly, lower risk to those around or involved in the system, and allow the system to have a longer life. However, there is a point reached while adding more regulation where detrimental or even self-destructive effects can occur. In Maxwell’s example, the machine would “become an oscillating and jerking motion, increasing in violence” until the physical governor could no longer govern.

That critical zone of too many compliance mandates in business and government systems manifest themselves in undesirable behavior in a couple of ways. One is that the resources to comply with the additional regulations are simply not there. That is, not everything can be complied with if the business is to stay in business or the government process is to continue to function. That means that choices must then be made on what gets complied with. And that means that the entity that is supposedly being regulated is now, by necessity, making its own decisions — independent of regulators, whether directly or indirectly — on what it will comply with and what it will not comply with. That, in itself, is not providing particularly helpful control. Worse, the organization might choose not to do those early compliance rules that were actually helpful.

Another way that too much compliance can have unintended consequences on the system is that if the organization does actually try to comply with everything, redirecting as much of its operating resources as necessary, can in fact bleed itself out. It might go broke trying to comply.

This is not to say that some entities should be allowed to be in business if they don’t have a business model that allows them to support essential regulation. Again, there is some core level of regulation and compliance that serve the common good. However, there is a crossable point where innovation and new opportunity start to wash out because potentially innovative companies, that might add value to the greater good, cannot stay in the game.

Axl, Izzy, Slash, Duff, & Steve on Mr. Brownstone from the album Appetite for Destruction, Guns N Roses

The line above, from the Guns N Roses song, Mr. Brownstone, comes to my mind sometimes when thinking about compliance excess, tongue in cheek or not. The song is a dark, frank, (and loud) reflection on addiction. The idea is that a little of something provided some short-term benefit, but then that little something wasn’t enough. That little something needed to be more and more and quickly became a process unto itself. Of course, I’m not saying that excessive compliance = heroin addiction, but both do illustrate systems gone awry.

So where is the stopping point for compliance, particularly in cybersecurity? When does that amount of regulatory activity, that previously was helpful, start to become too much?

I don’t know. And worse, there’s no great mechanism to determine that for all businesses and governments in all situations. However, I do believe that independent small and medium-sized businesses can make good or at least reasonable decisions for themselves as well as the greater good for the community. I would suggest:

I believe that the nature of our system in the US is to become increasingly regulatory, that is additive, and more taxing to comply with. However, we still need to know what the rules are and what the law is. From there, I believe, what defines the leadership and character of the small to medium size business or government entity is the choices that we make for ourselves and the greater good of the community.

[Governor & Maxwell Images: WikiMedia]

[Rolling Stone cover image: http://www.rollingstone.com/music/pictures/gallery-the-best-break-out-bands-on-rolling-stones-cover-20110502/guns-n-roses-1988-0641642]

Communicating risk requires identifying the right language for the right audience. While your experience may be in technical systems and all of the things that can go wrong with them, trying to communicate risk in technical terms to business leaders is generally a futile endeavor. There are a couple of reasons for this:

1) Technical systems and the risk issues that go along with them typically are heavily jargon-laden and without a lot of reference points to the outside world.

2) Everybody has limited bandwidth for talking about risk. You’ve got a very narrow window in which to communicate the issues.

That second point is one of the best pieces of advice that I’ve ever received regarding communicating risk. No matter how good your message may be, there is a finite amount of tolerance that people have to discuss risk in a given discussion. Exceed that window and you’ll be able to hear the clunk as their eyes roll into the backs of their heads.

All the more reason for choosing your language carefully. So, instead of techno-speak, when talking to business leaders, speak in terms of things that are meaningful to them. Depending on your background, this preparation may require a little bit of work on your part. What information products/services (eg reports, databases, workflows, etc) do they count on to do their work? What things do they count on to look good to peers and bosses? (This one may sound childish, but it’s not. It’s got a solid foothold in Mazlow’s hierarchy of needs).

Once you’ve identified what those needs are, you can work backwards to what information systems support them and what risks are associated with those technical systems. Techno-speak with the people supporting these systems is okay, that’s their language. But when communicating risk to business people (possibly to get funding to support your risk mitigation), you’ve got to speak their language.

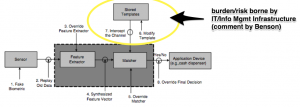

The Downloads page has a pdf of this graphic.

Kamala Harris, Attorney General, California has posted some pretty good cybersecurity advice for small and medium sized businesses (SMB’s) in that state.

California has 3.5 million small businesses which represents 99% of all employers. The report states 98% of their SMB’s use wireless technology of some sort, 85% use smartphones, 67% using websites, 41% on Facebook, and 36% using LinkedIn. I would speculate that other states, while not as large, probably have similar percentages of types of technology use.

The document covers threats such as social engineering scams, network attacks, physical attacks, and mobile attacks as threats to SMB’s in that state. Overviews of data protection and encryption, access control, incident response, and authentication mechanisms are also provided.

The core tenets espoused by the document are:

This document does a great job of providing an overview of cybersecurity issues and initial effort prioritization for SMB’s. It would be great to see other States follow their lead.

Carl von Clausewitz, Prussian General, famed war theorist, member of the OQBLRC (Often Quoted But Little Read Club), and author of On War makes this statement in Chapter 3 of On War:

“Our knowledge of circumstances has increased, but our uncertainty, instead of having diminished, has only increased. The reason of this is, that we do not gain all our experience at once, but by degrees; so our determinations continue to be assailed incessantly by fresh experience; and the mind, if we may use the expression, must always be under arms.”

Sounds a little bit like what we are trying to do today with information security and risk management, doesn’t it? In spite of massive amounts of information, we actually have more uncertainty. We’re less well-positioned to make good decisions and we’re less confident when we make those decisions.

In information security and risk management, we are constantly learning. While there is some common ground over time, this year is different from last year, this month is different from last month. There are relentlessly new attack techniques, new tools, new players, new alliances, new motivations, new targets, and new vulnerabilities. We are in the position of perpetual learning. In Clausewitz’ words, “we do not gain all our experience at once … [we] are assailed incessantly by fresh experience.” While a different context, I think we can heed Clausewitz’ advice that “the mind … must always be under arms” in our modern cybersecurity environment.

However, not to despair …

If we can extend the metaphor of kinetic battle a little bit further, Clausewitz tells us that, in the middle of the fur ball of confusion and uncertainty, there are moments of brief understanding of the greater gestalt, though, and that these moments are stepping stones to truth that can guide us in decision making. This has been called coup d’oeil by the French, Napoleon among others, — “There is a gift of being able to see at a glance the possibilities offered by the terrain…One can call it the coup d’œil militaire and it is inborn in great generals.”

I don’t know that we have ‘great generals’ in cyberwarfare, privacy, and business security yet, but I believe that this metaphor suggests that there could be. These are the few that simultaneously see more deeply, more broadly and are resolute in their decisions. Which brings us to ‘resolution’…

Clausewitz says that resolution is what removes “torments of doubt and the dangers of delay when there are no sufficient motives for guidance.” For those of us in the business of information security and managing risk, that is akin to acting with intention even while knowing that we have incomplete information. And we always have incomplete information. However, what often happens in the presence of partial information and the uncertainty that it generates, is that no action is taken or undirected action is taken.

Clausewitz is saying that having that capacity for coup d’oeil — that fleeting glimpse of the comprehensive picture — the great generals then act with intention and resolution to effect their purpose.

Maybe that will be the same with cybersecurity as well, that great generals and leadership will make the difference.

[Image: WikiCommons]

Georgia Tech has opened a center for the development and application of Internet of Things technologies. In addition to technical aspects, the center promises focus on ethics, privacy, trust, regulation, and policy.

Georgia Tech has opened a center for the development and application of Internet of Things technologies. In addition to technical aspects, the center promises focus on ethics, privacy, trust, regulation, and policy.

Trusteer, an IBM subsidary, has a couple of telling infographics regarding Java-based malware:

Remember the old ad line, “Sell the sizzle, not the steak” ? There seems to be a lot of that going on with biometric systems. There’s all kinds of excitement about what new body part can be quantified and its near-holy-grail-ness for authentication (the sizzle), but not a lot of talk about the infrastructure required (the steak) to provide the sizzle. By default, the cost of the steak falls back to the customer, the implementer of the biometrics system.

Remember the old ad line, “Sell the sizzle, not the steak” ? There seems to be a lot of that going on with biometric systems. There’s all kinds of excitement about what new body part can be quantified and its near-holy-grail-ness for authentication (the sizzle), but not a lot of talk about the infrastructure required (the steak) to provide the sizzle. By default, the cost of the steak falls back to the customer, the implementer of the biometrics system.

Interest in biometrics systems for authentication — sensing fingerprints, iris scanning, voice, other — continues to accelerate for several reasons:

Biometrics systems require several functional, secure, and integrated components to work properly with appropriate privacy requirements in mind. They need a template to structure and store the biometric data, secure transmission and storage capabilities, enrollment processes, authentication processes, and other components. These backend systems and processes, the steak, can be large, complex, and require real oversight and resources. For example, the enrollment process (getting someone’s biometric profile, aka template, into the database involves multiple, if quick, phases — sensing, pre-processing, feature extraction, template generation, etc.)

Like all systems, there are many points of attack or places where the system has some vulnerabilities as indicated in this vulnerability diagram in a paper by Jain, et al in this article.

While there are many points of failure (again as in all systems), the infrastructure component lies squarely with the customer. Its cost will show up as required enhancements, resources, and staffing to support the additional required infrastructure or it will show up as the cost of unmitigated risk.

Biometric Template Security: Challenges & Solutions. Jain, Ross, Uludag. (comment by author) http://bit.ly/1fWC21i

The infrastructure cost (or cost of unmitigated risk) occurs because the user’s biometric profile has to be stored somewhere and has to be transmitted to that somewhere and all the other things that we sometimes do with data — backup locally, backup at a distance, audit, maybe validate, etc. That profile data is the data that is used for comparison for a new real-time scan when someone is trying to unlock a door, for example. It is the reference point.

Because biometric data is about as personal as you can get, way more personal than a Social Security Number or credit card number — you can change those after all — that personal profile data needs to be highly protected. So that means that, at a minimum, you’ll probably want to store the profile encrypted and also transmit the data in encrypted sessions. That’s generally an IT infrastructure function, not a biometric device function.

When considering purchase of a biometric system, a partial list of things to consider might include:

Whether the biometric system includes just the sensing endpoint device or has backend support to include database and application support, it is critical that the customer knows where the biometric system infrastructure ends and where their own infrastructure begins and has to carry the burden of the new biometric system implementation.

To ensure privacy and security, someone has to pay for the steak that provides the sizzle. It’s best to figure that out who’s going to do that ahead of time.

Other reading:

[Eye Image: licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.