There is an apocryphal anecdote that a frog can be boiled to death if it is placed in a pan with room temperature water and then slowly heating the water to boiling. The idea is that the frog continues to acclimate to the new temperature which is only slightly warmer than the previous temperature (if the temp went up in incremental chunks) and so it is never in distress and never tries to jump out. A less PETA-evoking metaphor is that of a ‘shifting baseline’ which was originally used to describe a problem in measuring rates of decline in fish populations. The idea here is that skewed research results stemmed from choosing a starting point that did not reflect changes in fish populations that had already occurred which resulted in an order of magnitude of change that was not accounted for.

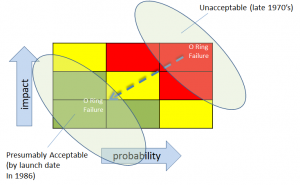

We can also see this sort of effect in risk management activities where risks that were initially identified with a particular impact and likelihood (and acceptability) seem to slide to a new place over time on the risk heat map. This can be a problem because often the impact and the probability did not change and there’s no logical reason for the level of risk acceptability to have changed. I believe this slide can happen for a number of reasons:

- we get accustomed to having the risk; it seems more familiar and (illogically) less uncertain the longer we are around it

- we tell ourselves that because the risk event didn’t happen yesterday or the day before, then it probably won’t happen today either. This is flawed thinking! (In aviation we called this complacency).

- we get overloaded, fatigued, or distracted and our diligence erodes

- external, financial, and/or political pressures create an (often insidious) change in how we determine what risk is acceptable and what is not. That is, criteria for impact and/or probability is changed without recognition of that change.

Challenger Disaster

Challenger plume after explosion

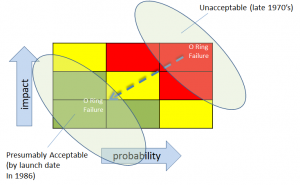

In 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded 71 seconds after liftoff. The Rogers Commission, established to investigate the mishap, created a report and panel debrief to include the testimony by the iconic Richard Feynman. Chapter 6 of the report, entitled “An Accident Rooted in History” opens with, “The Space Shuttle’s Solid Rocket Booster problem began with the faulty design of its joint and increased as both NASA and contractor management first failed to recognize it as a problem, then failed to fix it and finally treated it as an acceptable flight risk.” (italics added) Let’s recap that:

- initially failed to formally recognize it as a problem (but later did)

- failed to fix it

- morphed into an acceptable flight Risk

When further testing confirmed O Ring issues, instead of fixing the problem, “the reaction by both NASA and Thiokol (the contractor) was to increase the amount of damage considered ‘acceptable’.” That is, in effect, they changed criteria for risk. Implicitly, and by extension, loss of life and vehicle was now more acceptable.

For risk to become acceptable, the criteria for impact and/or probability would have had to change — even if implicitly

Physicist Richard Feynman, on the Commission, observed:

“a kind of Russian roulette. … (The Shuttle) flies (with O-ring

erosion) and nothing happens. Then it is suggested, therefore, that

the risk is no longer so high for the next flights. We can lower our

standards a little bit because we got away with it last time. … You

got away with it, but it shouldn’t be done over and over again like

that.”

This is the sort of frog boiling or baseline shifting that we talked about earlier. Though there were many contributing factors, I believe that one of them was that they simply got familiar with and comfortable with the risk. In a way, the risk was ‘old news’.

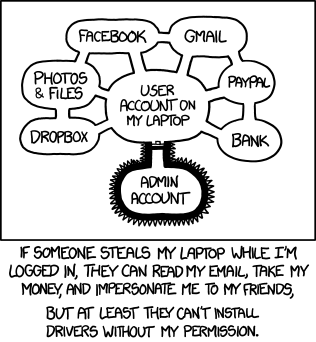

Frog Boiling in Information Risk Management

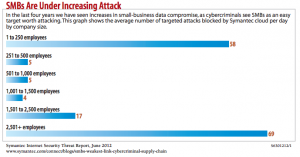

This kind of frog boiling or baseline shifting can happen with Information Risk Management as well. As we become inundated with tasks, complexity, and knowledge of new threats and vulnerabilities, it can be tempting to reduce the importance of risk issues that were established earlier. That is, we can have a tendency to put a higher priority on the issue(s) that we have been most recently dealing with. If we are not careful, the perceptions of earlier risks can actually change. Gregory Berns discusses perception change in his book, Iconoclast.

It’s one thing to consciously re-evaluate our tolerance for difference types of risk because we have new information and new things to consider, but it is another to let our tolerance for risk slide because of fatigue, ‘information overload’, political pressure, or distraction.

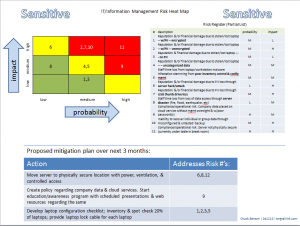

More than once I’ve picked up an older Information Risk Register & Heat Map and reminded myself that there were unmitigated risks that were still there. Yes, since that time, I had new risks to deal with, but that didn’t mean that the original ones went away.

One way to help us address this non-overt perception change is to use our earlier Risk Registers and Heat Maps.

- Look at it again.

- Did the original issues really go away?

- Did their impacts or likelihoods really lessen?

It may well be that with new knowledge of threats, vulnerabilities, and capabilities, that we have to revisit and adjust (usually increase) our tolerance for risk given our limited resources. That is fine and appropriate. However, this needs to be a conscious effort. Changing the importance of a risk issue, whether it be its impact or probability, because we are tired, overwhelmed, or because the issue is ‘old news’ doesn’t help us. We need to be methodical and consistent with our approach. Otherwise, we are just fooling ourselves.

Have you had to change your risk tolerance in your organization? Have you had to change your criteria for impact and probability? What were driving factors for re-assessing how you measure risk impact?