We have a love-hate relationship with risk and uncertainty. We hate uncertainty when it interferes with us trying to get things done such as projects we are trying to complete, programs we are developing, or things that break. We love it because of the excitement that it brings when we go to Las Vegas, or a enjoy a ball game, or watch a suspenseful movie. There’s uncertainty and risk in all of these, but that is what makes it fun and attracts us to them.

When we think of risk and uncertainty in terms of our IT and Information Management projects, programs, and objectives, and the possibility of unpleasant surprises, we are less enamored with uncertainty.

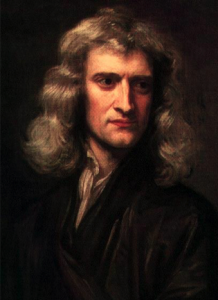

Why do we have a hard time managing uncertainty and incorporating risk-based analysis into our day-to-day work? We’ve already talked some about resource constraints that can make information risk management challenging, particularly for small and medium-sized businesses. However, there is a deeper issue that stems from over 300 years of human thought. In a nutshell, we just don’t think that way. Why is this? Who got this ball rolling? Isaac Newton.

Newton

In 1687 Isaac Newton lowers uncertainty and increases predictability with the publication of Principia

Isaac Newton (1642 – 1727) published Principia in 1687. In this treatise, Newton’s three laws of motion were presented as well as the law of universal gravity. This was a huge step forward in human knowledge and capability. Application of these laws provided unprecedented predictive power. The laws separated physics and philosophy into separate professions and formed the basis of modern engineering. Without the predictive power provided by Principia (say that three times real fast), the industrial and information revolutions would not have occurred.

Now, for the sneaky part. The increased ability to predict motion and other physical phenomena was so dramatic and the rate of knowledge change was so rapid that the seeds were planted that we must be able to predict anything. Further, the universe must be deterministic because we need only to apply Newton’s powerful laws and we can always figure out where we’re going to be. Some refer to this uber-ordered, mechanical view as Newton’s Clock.

A little over a century later, Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827) takes this a step further.

Laplace

Pierre-Simon Laplace ups the ante in 1814 and says that we can predict anything if we know where we started

In his publication, A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities (1814), he states:

We may regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its past and the cause of its future. An intellect which at a certain moment would know all forces that set nature in motion, and all positions of all items of which nature is composed, if this intellect were also vast enough to submit these data to analysis, it would embrace in a single formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the tiniest atom; for such an intellect nothing would be uncertain and the future just like the past would be present before its eyes.

In other words, Laplace is saying:

- if you know where you started

- if you have enough intellectual horsepower

- then if you apply Newton’s laws

- you’ll always be able to figure out where you’ll end up

Now, almost 200 years later, we’ve got enough experience to know that things don’t always work out as planned. That is, as much as one may desire certainty, you can’t always get what you want.

Jagger

The problem is that we largely still think the Newtonian/Laplacian way.

Even after the practical and theoretical developments of the last century, eg Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, the unknowability in Schrödinger’s Wave Equation and Godel’s Incompleteness, we still think the old school way on a day-to-day basis.

This gets reaffirmed in our historical IT service experience as well. We are used to systems having strong dependencies. For example, to set up a traditional content management system, there had to be supporting hardware, there had to be a functional OS on top of that, there had to be a functional database, and there had to be a current CMS framework with supporting languages. This is a very linear, dependent approach and configuration. And it was appropriate for simpler systems of the past.

Complexity Rising

The issue now is that our systems are so complex, with ultimately indeterminate interconnectivity, and systems are changing so rapidly that we can’t manage them with hard dependency mapping. Yet our basic instinct is to keep trying to do so. This is where we wrestle with risk management. It is not natural for us. Newton and Laplace still have a big hold on our thinking.

Our goal is to train ourselves to think in terms of risk, of uncertainty. One way to do this is to force ourselves to regularly apply risk management techniques such as management of a Risk Register. Here we write down things that could happen — possibilities — and also estimate how likely we think they are to occur and estimate their impact to us. When we add to and regularly review this list, we begin to get familiar with thinking and planning in terms of uncertainty.

We have to allow for and plan for uncertainty. We need to create bounds for our systems as opposed to attempting explicit system control. The days of deterministic control, or perceived control, are past. Our path forward, of managing the complexity before us, is to learn to accept and manage uncertainty.

How do you think about uncertainty in your planning? Do you have examples of dependency management that you can no longer keep up with?

I completely agree with your statement that “we just don’t think this way.” We are no “economic man.” Other factors, such as social acceptance, selfishness, pride, seem to drive our decision making more than a rational analysis of risk and probability. A project can fail (e.g. no one uses it, it is unsupportable, etc.) and the sponsor, vendor, and team may still be viewed as heroes by those who “count.” It would be quite refreshing to start a project with an honest description of the success criteria, such as “we spend all of the budget allocated so my vice president thinks I am doing something.” And then populate the risk register with real and relevant risks, “We can’t hire contractors fast enough to meet our burn rate.” If we can build a culture that somehow acknowledges the emotional motivations as well as the more rational ones, perhaps we can have a real and relevant discussion about risk.